My Year of Blogging Shamelessly: Part Two of Six

One woman’s journey from her body to her soul letting her relationship with food show the way.

My mum had had a handful of boyfriends since her divorce. Not a high number for a single woman, but for a girl who missed her dad, who liked the men her mum was with, and who was devastated every time one of her relationships ended, it was too many. It was like having my already tentative heart opened only to have to close it again—hardened with a new layer of scar tissue each time.

To make matters worse, my dad was not someone I could rely on emotionally. I learned in adulthood that he spent grade five and grade eight in care with the Catholic Church in Moose Jaw and in Edmonton. I have heard stories that my grandparents drank a lot and partied a lot, and were desperately poor. My dad won’t say much about that time except “you knew which priests to stay away from.” But his elder sister recounts memories of neglect at home and being left for long periods of time in the convent. On the occasions when she was finally picked up by her parents, she would arrive home only to meet new siblings.

My dad is a much better parent to adult children. I get that. And in my youth, when I needed him most, he was carrying a lot of shame from my mum’s leaving him. That likely only exacerbated the scars from his own parents’ eventual divorce. One thing I knew then, my mum was all I had.

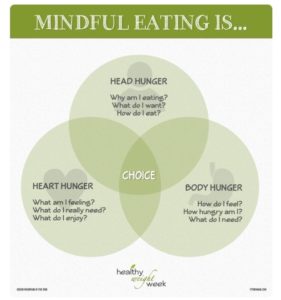

So I gained weight with the onset of puberty. I would lose the weight either by dieting or during times when my home life with my mum felt stable. At 17, I discovered a book called Thin Within, which explained the principles I call intuitive body eating or hunger eating: eat when you’re hungry, eat what your body wants, stop when your hunger goes away. The philosophy maintained that if you follow this way of eating, your body will land at its natural size. If you are resistant, then there is emotional work to do.

(And if you are feeling comfortably removed from this discussion because “you watch your weight” or “you are careful about what you eat,” realize that emotional resistance equally applies to not eating when you are hungry. Dieting, for example—and its extreme manifestations of anorexia and bulimia—is simply the flip side of coin. Do you deal with feelings of fear, anxiety and overwhelm by eating to dull them or by abstaining from eating to control them? Either way, you are anesthetizing yourself. In the words of Geneen Roth, writer on women and food: in the former instance you are a permitter, the latter instance you are a restrictor. With the latter, we cope with our overwhelming experiences by managing something smaller, easier like our body and our hunger. That is, we hyper-control meaningless things in our world when we feel overcome by the meaningful ones. Similar to sudden “important” cleaning and organizing when we should be studying for an exam. With dieting, we ignore our hunger signals [and what our bodies want] not by numbing them but by overriding them.

If you are open to being courageous, ask yourself this question: are you letting your body determine the parameters of your eating experience? Are you listening and tending unreservedly to its cues as its needs? Or does that prospect scare you? Your answer to the question is an existential, spiritual litmus test of your personal state. It reveals how much you believe you can trust the world around you to support and sustain you and how worthy you deem yourself to be as you engage in it.)

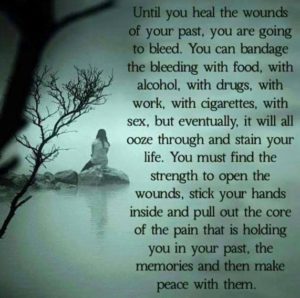

This approach helped me discover a deep sense of knowing within myself. I recognized it as wisdom that I felt even then would guide me for the rest of my life. I embraced the principles. But as effective as they were for a while, the information wasn’t enough to get me through times when I was in emotional danger and overwhelmed by a sense of abandonment. When I needed support and there was no one I trusted to give it to me. Like the time my mum had a new boyfriend after having been single for a year, a year in which I had thrived. She started a relationship with a much younger man. He was halfway between our ages. I really liked him at first. But their relationship became tumultuous, which wreaked havoc in my life.

***

Because of vulnerability’s fundamental role in a truly fulfilled life, Brené Brown decided to study it. Two important themes emerged from her research. The first is that we need to see through the idea that vulnerability is weakness. In fact, the exact opposite is true. Vulnerability is the most accurate measurement of courage there is, and it is courage that takes us where we most want to go. But so many of us won’t sit with it. We tell ourselves that we don’t do vulnerability—either because it is not our in our gender, personality type or genetic makeup, or because the family, professional, ethnic group we belong to doesn’t do it. When we catch glimpses of it in ourselves, we decide there is no way we are going to feel it. No one can make us! So we put on armour, literally in the case of fat. But here is the thing: how is that working for you? Are you happy? Are you fulfilled? Or do you want something more? Do you want to feel alive?

For Brown, most of us who aren’t feeling vulnerability are actually just numbing it. She believes this is why we are part of the most indebted, obese, medicated and addicted generation ever. In her opinion, it is not the big ways that we need to worry about. It is the day-to-day ways we are “taking the edge off” of our lives with everything from a glass or two of wine in the evening to sugary treats and our smart phones. Why talk about this? Because we cannot selectively numb. The good stuff goes out with the bad. Then we feel empty. So we numb some more.

For Brown, most of us who aren’t feeling vulnerability are actually just numbing it. She believes this is why we are part of the most indebted, obese, medicated and addicted generation ever. In her opinion, it is not the big ways that we need to worry about. It is the day-to-day ways we are “taking the edge off” of our lives with everything from a glass or two of wine in the evening to sugary treats and our smart phones. Why talk about this? Because we cannot selectively numb. The good stuff goes out with the bad. Then we feel empty. So we numb some more.

What her research found is that the people who are willing to bear vulnerability live from a deep sense of worthiness, meaning only that they believe they are inherently worthy of love and belonging. It is a sustaining sense of being enough. This does not mean they believe they are everything. They don’t puff up. But neither do they shrink. They don’t hedge their bets, they don’t close their hearts. They simply stand their sacred ground. They understand that vulnerability is neither good nor bad, it is just necessary. This allows them to go into “the arena” courageously, wholeheartedly.

Brown muses on the irony of the myth that vulnerability is weakness. Vulnerability may be least of what we want to show other people of ourselves. But it is most what we want to see in other people. It draws us to them. Yet, we are afraid to let ourselves be as seen as deeply. In the process we rob ourselves of what connection has to offer.

***

At a particularly rocky time between my mum and her boyfriend, when I was still 17, he informed me that he could tell by the way I looked at him that I wanted to have sex with him. Moreover, that I needed to know that this was never going to happen between us. I was puzzled, confused by this assertion. So I went to my mum in protest, to get things straightened out. To get him in trouble! Instead, she responded that they had thought I’d had a crush on him, that I needed to have the boundaries drawn. That he should do it.

I felt betrayed. Like I had been hung out to dry. It was a combination of gutted and then ashamed and afraid. From my adult perspective, I believe she felt threatened by me given the age disparity between the two of them. She didn’t want to see his attraction to me. So she made me the scapegoat. I lost her that day. Or maybe she lost me.

Then, a couple of months later, for whatever crazy reason, my mum asked her boyfriend to move in with us. Shortly after that, I gained a huge amount of weight. And I gained quickly. In fact, there were instances in which I was unrecognizable to myself when I saw my reflection in a mirror. I still have stretch marks on my body from the rapid and substantial change in my body. During that time, I only remember a few people expressing any concern. One of them was my grade 12 chemistry teacher. When he asked me if there was anything wrong, I balked—I was in a form of denial myself and hadn’t conceived of the possibility of a trustworthy adult.

I mean, what could have been done? It seemed easier for me to remain “the problem” in my family. Not rock the boat. After all, it hadn’t worked out very well the last time I tried to talk to my mum. I believe my weight gain was a subconscious strategy to neutralize the threat of my attractiveness to my mum’s boyfriend by both getting fat and hating myself. I went to that teacher nine years later to thank him for noticing my pain. I cried as I thanked him. That came as a surprise to me. To that point, I hadn’t consciously registered the depth of it. Most people just mocked me for being fat and told me I needed a diet. That left me feeling ugly and unlovable. The prospect of eating when I was hungry and stopping when I had enough did not feel safe. I needed food to quell anger and provide me with safety and comfort.

Beautiful Michelle. ?

Thank-you Kelli.

The potency of your truth and sharing is life-changing. Thank you.

Thank-you Christina, I appreciate that my words have had impact.

I love this blog. I wear my vulnerability like a “kick me” sign on my back. The older I get, the more people follow the instruction without thought. ‘You were the one wearing the sign’ they say. So I own it and carry on, because it’s as much a part of me as the compassion it takes to wear it.

Your words are powerful, Liana. Thank-you. I was thinking about what you’ve said in terms of your vulnerability in the world for you. Have you read Brené Brown’s Daring Greatly? I feel that chapters 3 and 4 are helpful in providing insight to find the balance between what to show of ourselves and when to protect our tender parts.

Thank you Michelle. Actually, I’ve discovered the amazing Brené Brown through your web site and just finished “Men, Women, and Worthiness”. I plan on reading all her books, including “Daring Greatly”. The book from your site that changed my life in the most amazing way, however, was “A Return to Love” by Marianne Williamson. While it was hard to read at the start because I’m not a big Christianity fan, I just substituted my own words in my head (Gord for God, and so on….) and it worked 🙂 I just went through a major incident with a guy (I’m 49 and single) that hit the heart of my personal shame. “A Return to Love” spoke directly to me; even the examples were spot on with my life. I love it when a book is timed so perfectly in my life that it feels like the Universe wrote it just for me 🙂 Like a hug and a head-pat from “Gord”. LOL Thank you for your wonderful site!

Liana, I adore Marianne Williamson’s book Return to Love. I am glad you found it and I am glad it spoke to you. I feel some baggage sometimes around the word God, so I often say “Universe.” “Gord” is great too. Do you know her piece on shining our light? She says it is not our darkness that scares us, but our light. We ask ourselves, who are we to be talented, gorgeous, successful? She asks us, who are we not to be? We can give ourselves permission to be biggest selves and live up to our greatest potential. Beautiful. Thank-you for your lovely words about the site. Always appreciated.

Wow Michelle, this is so beautiful, heartbreaking, and inspiring all at the same time.

Thank-you Patricia. It is all that, and I am happy that comes across in equal parts.

thank you Michelle. ❤️

Love back.

“Gord is great..” That’s pretty funny. A bumper sticker perhaps? It would be funny to see how many “oh no she di’in’t” reactions it gets. LOL Thank you for the “shining our light” notes. I’m going to read them over and over to remind myself that me not being good enough did NOT create the economic nightmare I’m struggling to cope with. 😉